Why Japanese Spirituality and Religion Is, and Isn’t, Part of Life

via Moyan Brenn

“I’m a member of the Nichiren Buddhist sect,” a friend told me. “But I’m an atheist.”

Despite how contradictory that is to the non-Japanese mind, it’s similar to how most Japanese feel. The majority of Japanese feel that having a religious or spiritual attitude is important. They visit Shinto shrines on holidays and observe Buddhist funerals, but the overwhelming majority still consider themselves atheists. Japan just has a different idea about what “religion” is.

Shinto is a Religion, But Doing It Isn’t

via Moyan Brenn

Kanzaki Nobutake, a Shinto priest, once wrote in his autobiography that he had no religious belief. The idea of atheist clergy wouldn’t sit well with most faiths, but while the rest of the world considers Shinto a “religion,” in Japan, Shinto is generally seen only as Japanese tradition. In a sense, being Shinto is “being Japanese,” although that’s much too broad a brushstroke, so don’t take it too literally.

One of the most important traditions in Japan is going to a Shinto shrine on New Year’s to pray for the upcoming year. Likewise, many other holidays or events involve a trip to a shrine. But just because someone prays at a shrine or receives a blessing from the priest doesn’t mean they follow Shinto.

Religion is a Private Matter

via Steven Depolo

The idea of Shinto as tradition began during the Meiji era, when the government created State Shinto, a national quasi-religion that presented the emperor as a living god. Japan wanted to create a theocracy, but also had to appease western powers by securing freedom of religion. There were two answers. One was to ensure freedom of religion, but with the stipulation that it had to be neither “prejudicial to order and peace” nor “antagonistic to a person’s duty as a subject.” Meaning, religion was free, but just so long as you kept it to yourself.

This mindset persists in Japan to this day. Even if a person is a believer in a faith or just spiritual, they probably won’t talk about it. If you bring up the topic of religion with someone who isn’t a close friend, it’s somewhat of a breach of etiquette that needs to be handled carefully.

It’s the Japanese Way

via MIXTRIBE

The Meiji government’s other answer was to change Shinto from a religion into “the performance of national rituals” and “the public way of heaven and earth.” During ceremonies, prayer was removed to uncouple it from religion. This helped changed State Shinto from a religion into part of just being a good Japanese citizen, which likewise had the effect of “dereligionizing” normal Shinto and transforming it into a part of Japanese culture.

A ceremony where rice is offered to a local kami (god) could be “religious” in nature, but it would also be considered just a local custom by probably everyone there, thus nonreligious. Religious rituals and festivals are observed in Japan, but are generally viewed as public traditions. So, if your Japanese friend does anything that appears religious, they may be a devoted follower, or more likely they are just following custom.

Spirituality is Living Normally

via Wonderlane

While Shinto equates to tradition for most Japanese, Japanese Buddhism also played a role in Japan’s religion by making living a normal life an acceptable way to behave spiritually. But it’s important not to think “Buddhism” when you think of it in Japan. Instead think “Japanese Buddhism,” which has a number of different basic tenants. Maybe you’ve heard this quote by Alan Watts:

“Zen does not confuse spirituality with thinking about God while one is peeling potatoes. Zen spirituality is just to peel the potatoes.”

Zen Buddhism implied that people could practice spirituality by doing normal things in their everyday lives. Some thinkers took this to mean that there was no need to pray or do any kind of rituals at all. While they may have meant to instead apply the concepts of Zen to everyday life, ideas like these had the effect of diminishing the value of Japanese religious customs.

Religious Ceremony

I was once at the Itsukushima shrine when I had the chance to watch a ritual blessing by a Shinto priest. Great, I thought, I get to see traditional Shinto in action. About two dozen people knelt on the floor as a priest came out onto the stage. He waved a blessing stick over the crowd, then disappeared back into his side room. As I waited to see what would happen next, the blessed began to rise, then leave.

Nothing came next. Is that it, I thought, but soon a group of dancers took the outside stage and began a traditional dance. I’d never seen anything like either of these two ceremonies before.

I mention it because Japanese are a lot like this in respect to other culture’s religions. While an atheist in the west, for example, may have a decent grasp of Christianity’s fundamentals, Japanese generally have very little knowledge about others beliefs. If you start a conversation with a Japanese person about spirituality, you may get some strange reactions.

At best it facilitates intercultural dialogue, like when my old students asked me why I won’t pray at shrines or temples. Then I ask them why they pray at both and we started a good conversation about how western religions don’t mix together like Shinto and Buddhism.

When Religion Matters

via George VII

But while religion plays almost no role in normal Japanese life, in death it’s a big deal. Ancient Shinto was the main faith in Japan, but since it regarded corpses as impure, it had no way of comfortably dealing with death. Buddhism became popular in Japan because it filled this hole with its funeral ceremonies.

Japanese funerals require a lot of ceremony. During funerals, the spirit of the dead relative “hears” a priest recite the sutras before them. That, and the family purchasing a Buddhist name to be bestowed on the deceased, ensures their enlightenment in the afterlife. Since the funeral is so critical to the quality of a person’s afterlife, it’s a huge deal in Japan. Even after the funeral itself there are ceremonies held to ensure the departed has a good afterlife, which can recur for years and years at great expense to the family.

I remember talking to a former student, a surgeon, whose father died. He was shopping around for places to bury him. Doing so meant that he had to officially join the Buddhist sect of whatever temple he chose, but for him the decision was purely financial. It had nothing to do with faith.

It may seem strange that despite having little belief in religion, Japanese have such strong beliefs in the afterlife. But the afterlife is the one thing that could be called a “religion” in Japan. Many homes will have a butsudan, a family altar, where the family makes offerings to their ancestors. While there is no doctrine or scriptures regarding ancestor worship, it is still a deeply engrained belief in Japan.

It’s Inseparable From Japanese Culture

Funeral ceremonies are a major concern for Japanese because everyone is concerned about their afterlife. But that doesn’t mean those beliefs touch their daily lives in any meaningful way. In ancient Japan, life was Shinto and death was Buddhist, and there was inevitably some overlap in the two faiths. Ancient Buddhism would even say that local deities had converted to Buddhism and become buddhas themselves, allowing locals to keep worshipping their own gods as buddhas. In a sense, this kind of Shintoism was Buddhism. But when Shinto later transformed into a public tradition instead of a religion, the religious aspects of Buddhism were likewise dealt a secular blow.

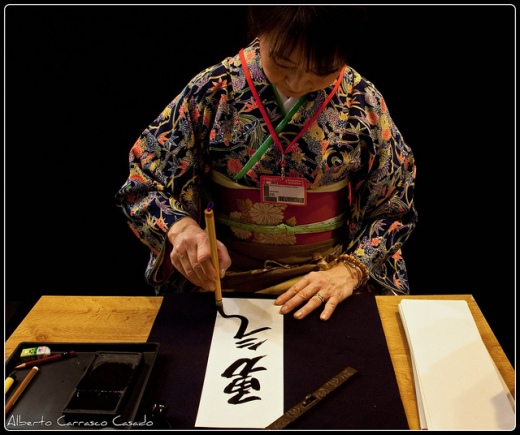

Like Shinto, many aspects of Buddhism were relocated to tradition. In the case of Zen Buddhism, primarily Zen, this revealed itself in the arts. Tea ceremony, ikebana, shodo, and many others things we associate with traditional Japanese culture were deeply influenced by Zen.

Spirituality is generally seen as a positive thing in Japan, but since it is so tied together with Japanese culture, it isn’t really “religion” so much as custom. The non-Japanese idea of “religion” is thought of as essentially that: non-Japanese.

It’s Not A Holy War

One surprising thing about religion in Japan is that you don’t see the hate about it you do elsewhere. I’ve never see an argument about faith here except between two foreigners.

In many parts of the world bringing up religion is like dropping a match onto a pile of dry leaves. But because religion is so intertwined with culture for Japanese, talking about another country’s religion is like talking about how Americans are individualist, or how Indian women dress so beautifully, or Brazilian Carnival, or the Islamic call to prayer. Religion is just another interesting facet that makes people and their cultures unique. It’s quite nice in that respect.

Maybe we could learn something.

The bit about Buddhist funerals quite intrigued me. Was that the main reason Buddhism grew in popularity in Japan, or are there others?

It took care of death, which was the practical reason most people took to it. The Shinto afterlife was a gloomy place kind of like Hades (not the fire and brimstone one, the actual Greek one,) so the idea of a Buddhist paradise appealed to most people.

That said, its spread was slow until Empress Suiko officially recognized it, making converting to the new religion “okay,” even fashionable. After that, it quickly started spreading across Japan on its own merits.

“If you bring up the topic of religion with someone who isn’t a close friend, it’s somewhat of a breach of etiquette that needs to be handled carefully.”

I’m not sure about that. Plenty of people here have asked me about my personal stance on religion, how I do/don’t practice it, and what I think of other religious practices and culture, and have seemed pretty okay with me asking similar questions in return. Some of these people have been friends, but most have been co-workers or more casual acquaintances. That said, it’s possible there’s a significant age gap going on, because everyone who I’ve had these conversations with have been… well, not necessarily young, but certainly well under retirement age – and I can imagine religion being a somewhat more taboo conversation topic among older generations.

Now that you mention it, those a generation or so older have been a lot more hesitant to talk about religion than younger. Although, it’s depended on the specific topic, actually. You’re making me wish I had included this in the post, lol.

Yeah, no one, old or young, has been unwilling to talk about religious customs: what you do during a ceremony, for a holiday, etc.. Most have been enthusiastic about sharing, actually. But almost everyone I’ve talked to about a generation or so older has been hesitant to take the next step and discuss what they actually do or don’t believe.

Also, even with younger people, I’m sure our foreignness plays a role in how comfortable Japanese are talking with us about some topics they normally wouldn’t with other Japanese. That’s definitely going to be a future post.

Thanks. I’ve been shopping around for basic information on Shinto and Japanese Buddhism as I plan another visit. You have helped me along that understanding.

I thought Shinto was a religion, but that isn’t the case. I’m looking for another quasi-religion, something I can relate to, that comes from Japan. 🙂